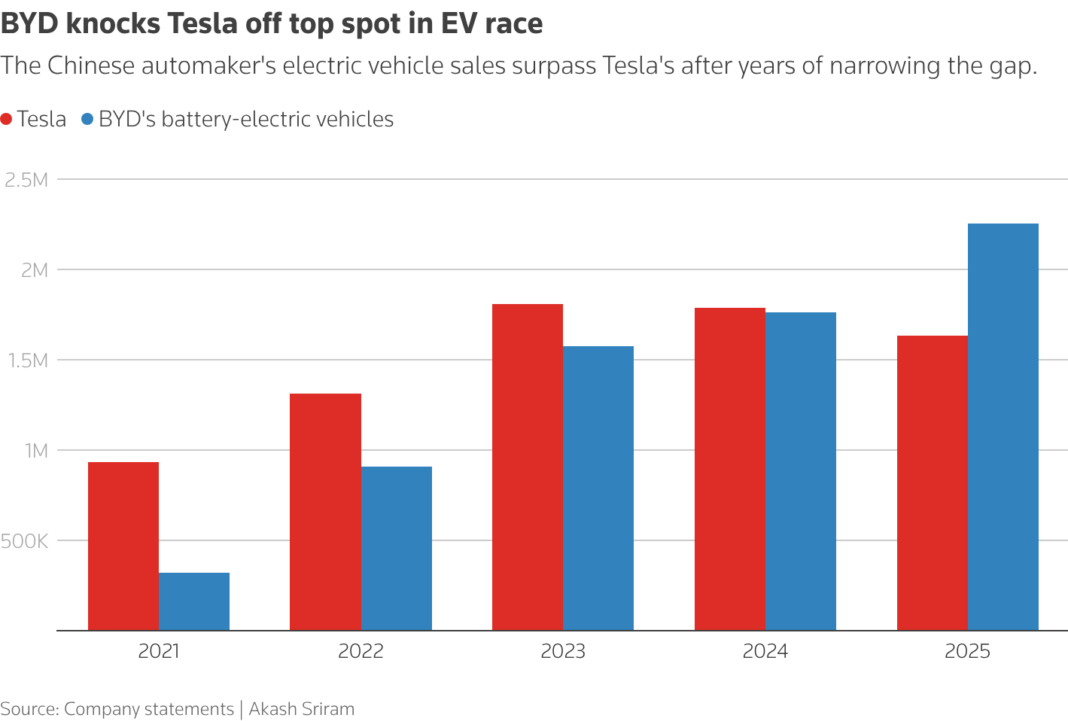

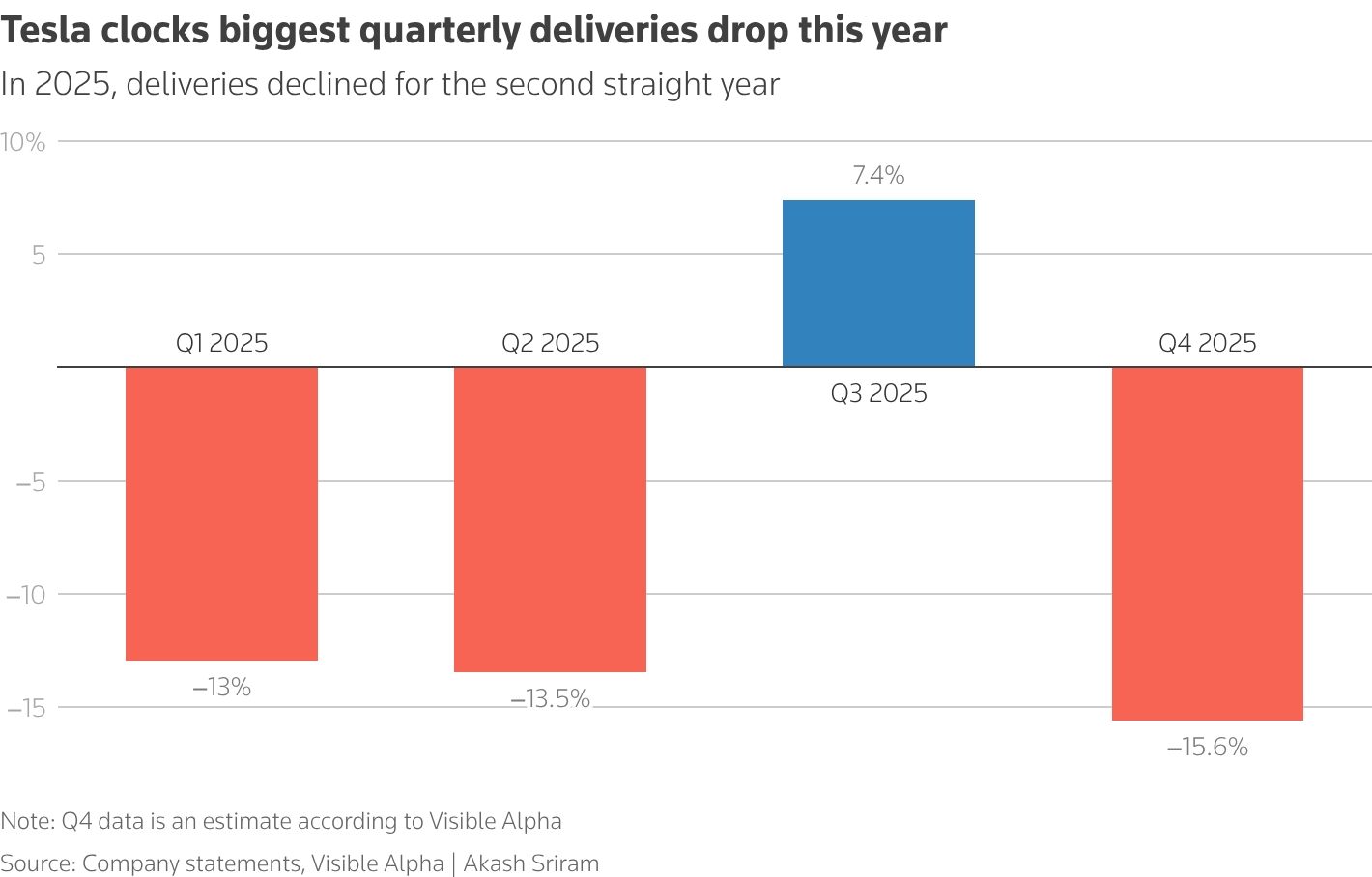

Tesla just posted numbers that would have been unthinkable two years ago: 418,227 vehicles delivered in Q4, down 15.6% from the same quarter last year and a full 70,000 units shy of what analysts expected. For a company that once moved the goalposts on demand every quarter, this marks the second consecutive annual decline—with 2024’s 1.64 million vehicles trailing 2023’s 1.79 million. As someone who’s watched Tesla defy gravity since the Model S days, I can tell you these aren’t rounding errors; they’re structural cracks in the growth story that made Elon Musk’s company the world’s most valuable automaker.

How the Tax Credit Expiration Became a Real Problem

The expiration of the $7,500 federal EV tax credit on September 30th didn’t single-handedly cause Tesla’s decline, but it exposed how much the company relied on artificial demand stimulation. Tesla bulls long argued that brand strength and the Supercharger network would insulate sales from incentive-driven purchases. That theory collapsed when Q4 deliveries accelerated their slide immediately after the credit disappeared, suggesting Tesla had been pulling future buyers forward—exactly what subsidy critics predicted.

The geographic breakdown reveals deeper problems. While U.S. deliveries absorbed the biggest hit from the tax credit loss, Tesla’s global numbers show weakness everywhere. China, once Tesla’s growth engine, has become a battleground where local competitors like BYD offer comparable range at 30% lower prices. In Europe, Tesla’s aging Model 3 and Model Y lineup faces fresh competition from legacy automakers who’ve finally mastered electric drivetrains. The result? An 8.6% annual decline that no amount of Full Self-Driving promises can obscure.

BYD Just Ate Tesla’s Lunch—and Dinner

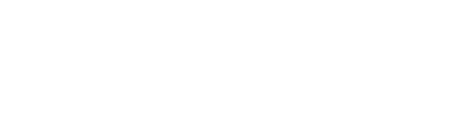

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable for Tesla faithful: BYD didn’t just outsell Tesla globally for the first time—they demolished them. With 2.26 million vehicles sold in 2025 compared to Tesla’s 1.64 million, the Chinese automaker proved that scale and affordability trump Silicon Valley mystique. I’ve driven both companies’ latest offerings, and while Tesla still holds an edge in software integration and charging speed, BYD’s blade batteries and platform flexibility represent a fundamentally different approach to EV manufacturing.

The numbers are brutal for Tesla investors who long dismissed BYD as a regional player. While Tesla’s deliveries contracted 8.5% year-over-year, BYD grew 28% in a global EV market that expanded by roughly the same margin. Translation: Tesla lost market share in a growing pie, while BYD captured the growth. More concerning for Tesla’s future, BYD’s expansion into Europe—historically Tesla’s strongest overseas market—shows no signs of slowing. The European EV market grew 15% in 2024, but Tesla’s regional deliveries actually declined.

What makes this especially painful is that Tesla should have seen it coming. BYD’s vertical integration strategy—manufacturing their own batteries, semiconductors, and even mining lithium—has created cost advantages that Tesla’s outsourced approach struggles to match. While Tesla was optimizing for autonomous driving capabilities that remain perpetually two years away, BYD focused on the unglamorous work of reducing battery costs and improving manufacturing efficiency. The market has rendered its verdict.

The Robotaxi Distraction That’s Costing Real Sales

Tesla’s response to these delivery misses has been quintessentially Musk-ian: pivot harder to future promises. The company’s October “We, Robot” event showcased steering-wheel-free vehicles that may not hit roads until 2027—if ever. Meanwhile, Tesla’s actual product lineup grows stale. The Model 3 debuted in 2017, the Model Y in 2020, and the Cybertruck’s production ramp remains glacial. Compare that to BYD launching six new models in 2024 alone.

I’ve covered enough tech companies to recognize this pattern: when current products lose competitiveness, promise revolutionary breakthroughs just over the horizon. The problem for Tesla is that mainstream car buyers—unlike tech enthusiasts—make rational economic decisions. A Model Y that costs $47,740 (after losing the tax credit) against a BYD Seal that offers 80% of the range for 60% of the price isn’t a hard choice for most families.

The market’s reaction tells the story. Tesla shares dropped 2% on the delivery miss, but what’s more telling is the trading pattern: retail investors who’ve held through previous volatility are finally selling into strength. Institutional money, meanwhile, rotates into traditional automakers who’ve solved their EV transition challenges. Ford’s Mustang Mach-E and GM’s Equinox EV both gained market share in Q4, proving that Tesla’s competitive moat was shallower than advertised.

The Robotaxi Mirage Is Getting Expensive

While Tesla’s delivery numbers cratered, Musk’s investor call doubled down on the robotaxi moonshot—promising a “cybercab” reveal later this year with no steering wheel or pedals. Here’s the problem: every quarter spent chasing autonomous vaporware is another quarter where Tesla’s actual product lineup ages into irrelevance. The Model 3 turns seven years old this summer; the Model Y is five. Neither has received a meaningful refresh while competitors like Hyundai’s Ioniq lineup and BMW’s Neue Klasse EVs are launching with 800-volt architectures, bidirectional charging, and interiors that don’t feel like 2018.

The opportunity cost is staggering. Tesla spent $3.1 billion on R&D in 2024, yet delivered essentially the same vehicles with slightly different wheel options. Meanwhile, Chinese competitors are iterating at smartphone speed—BYD rolled three new platforms in 18 months, each cutting battery costs by double-digit percentages. Tesla’s insistence that Full Self-Driving hardware baked into every car since 2016 will eventually justify premium pricing looks increasingly like a $10,000 per-vehicle tax on credulity.

| Metric | Tesla 2024 | BYD 2024 | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global EV Deliveries | 1.64M | 2.26M | -620K |

| Avg. Price (USD) | $47,500 | $28,300 | +68% |

| New Platforms Launched | 0 | 3 | -3 |

Supercharger Advantage Is Evaporating

Tesla’s charging network was supposed to be the moat that justified premium pricing even as specs lagged. That moat just sprung a leak. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory reports that non-Tesla fast charging ports in the U.S. grew 112% in 2024, while Tesla’s Supercharger expansion slowed to 23% as the company paused construction on 40% of planned sites. Electrify America, once a reliability joke, now matches Tesla’s 97% uptime according to DOE data.

More damaging: Tesla’s decision to open its connector standard (now NACS) effectively commoditized what was once proprietary. Ford and GM owners will get Supercharger access this year, but they’ll also discover that Tesla’s 250kW peak speeds are no longer class-leading. Hyundai’s E-GMP vehicles charge at 350kW, adding 100 miles of range in under five minutes—something no Tesla can match without the long-promised V4 Supercharger upgrade that’s been “six months away” since 2022.

The Margin Compression Reality Check

Here’s what keeps Tesla’s CFO awake at night: every vehicle Tesla doesn’t deliver in 2025 carries an average gross margin of $12,400, according to the company’s own Q3 filings. Multiply that by the 180,000 annual delivery shortfall versus 2023 levels, and you’re looking at $2.2 billion in lost contribution margin—before accounting for the fixed cost absorption that happens when factories run below 80% utilization. Tesla’s Fremont and Shanghai plants are now operating at 65% and 71% capacity respectively, triggering unit cost inflation that no amount of Chinese battery price declines can offset.

The pricing strategy is becoming desperate. Tesla cut U.S. Model Y prices four times in Q4 alone, totaling $7,500—the exact amount of the expired tax credit. But unlike 2023’s cuts that grew volume, these merely slowed the bleeding. Average transaction prices still fell 11% year-over-year while deliveries dropped 15%. That’s the textbook definition of pricing power collapse, and it explains why Tesla’s automotive gross margin has fallen from 28% in 2022 to 16.3% last quarter. When your brand can’t command premium pricing despite a five-year head start, you’re not a growth story anymore—you’re just another car company with bloated costs.

Tesla’s valuation premium always depended on two pillars: unlimited demand growth and technological moats that justified 30%+ automotive margins. Both pillars just cracked in the same quarter. The company that once claimed it couldn’t build cars fast enough now can’t sell the ones it builds. The “machine that builds the machine” is just another assembly line running below capacity, while competitors who actually iterate on product rather than promises are eating Tesla’s lunch across every price segment that matters for volume.